While the discovery of minerals and precious metals can build communities, it can also have significant benefits for donors

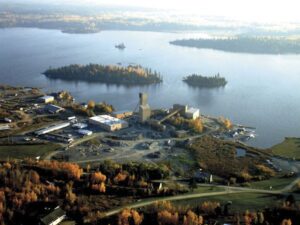

When Shawn Khunkhun arrived at a remote area of Manitoba, he remembers being employee number five. After years of prospecting and raising capital, it was time to drill a promising bit of a wilderness north of Winnipeg.

And low and behold – jackpot.

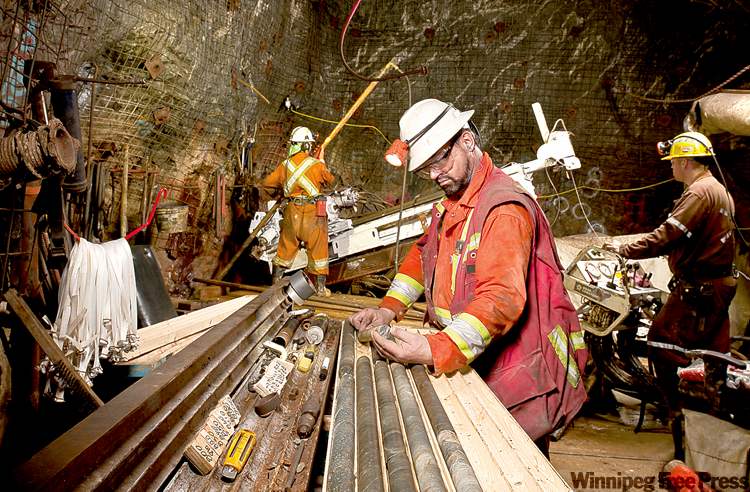

That’s the story of the Rice Lake Mine. In a place where there was nothing, a boom occurred. Khunkhun arrived in 2005 and left in 2011. During that time, the mine’s employment exploded to 600 workers, paying out an average salary of $100,000. Given the location of the mine in northern Manitoba, many of the workers were First Nations.

“We were a significant employer in the province,” he says, “built on the back of an exploration drill hole.”

Kunkhun, who is now the President and CEO of Stikepoint Gold in British Columbia, knows firsthand the transformational economic impact a hole in the ground can have.

He finds it exhilarating to work with the best scientists, explorers and engineers to come up with a strong business case for investors and shareholders. And it’s even more exhilarating when a discovery is made.

That’s why, over the last three years, Stikepoint has been buying up properties in north-western British Columbia and the Yukon, in search of the next Rice Lake Mine – a discovery that could bring major prosperity not only to citizens in the province, but also to the provincial government’s coffers.

But like Rice Lake Mine, first things first.

ABOVE: A geologist examines a drill core in the Rice Lake mine at Bissett.

Strikepoint Gold, like other junior mining companies, need to raise capital to explore for that next big deposit. The importance of companies like Strikepoint to the Canadian economy is not lost on the government. That’s why, since 1954, they have offered flow-through shares, to incentive Canadians to invest in these companies with a 100% tax deduction.

While seemingly unrelated, the purchase of flow-through shares is exactly why companies like The Foundation (WCPD) are able to help Canada’s largest donors give up to three times more to the charity of their choice, at no additional cost.

When a mining company like Strikepoint issues shares to raise funds, donors can purchase them for the tax benefits, and then immediately sell them at a discount to an institutional buyer, or liquidity provider, for cash. Thus, the donor does not take on the stock market risk.

The donors offer these cash proceeds of the sale to the charities of their choice and receive another 100% deduction for this donation.

By combining these two unique tax policies, Canadians can assist in the development of the economy, while also giving more to charities. How much more? This method of giving has resulted in hundreds of millions in donations for Canadian charities.

The government has promoted these two tax policies – both older than your RRSP, because it also understands the multi-faceted benefits to society.

“The life of a mining company is in exploration, and the best way to spend money on it is flow-through shares because the funds go 100% into the drilling and exploration,” said Farshad Shirvani, President and CEO of DoubleView Capital Corp, another company in the exploration phase for gold and copper in British Columbia.

Shirvani says he has raised millions for his projects using flow-through shares.

“BC is based on mining. It is the main artery of money into more remote communities, especially for First Nations. They need the job market and the money into their communities.”

At Telegraph Creek, for example, located off Highway 37 in Northern BC, is a mix of First Nations and other peoples. Shirvani says these communities are not as isolated as we might think.

“They have cell phones, like us. They are connected to the world. And they want to be more connected to the world,” Shirvani explains.

As for Kunkhun and Strikepoint Gold, his focus is now recruiting those first employees – geologists, drillers and other professions – so the company can inch that much closer to a discovery. One of the towns closest to his prospects is Stewart, BC, population of only 500. Back in the early 20th century, this city has a population of 10,000 when gold and silver was discovered in the area.

“Mining is everything up there. It is essential and it is the backbone,” he says. “What is exciting is the possibility of reinvigorating that.”