Arthur McDonald is unique in his appreciation for philanthropy.

After all, he wasn’t born a Nobel Prize-winning physicist. Before reaching the pinnacle of his profession in 2015, McDonald was the recipient of an endowed chair at Queen’s University, courtesy of philanthropists Gordon and Patricia Gray, giving him the opportunity to pursue cutting-edge research. Two years after it ended, he would accept the Nobel Prize.

But on Easter Sunday this year, another act of philanthropy would be particularly unique, and leave the eminent scientist “flabbergasted.”

It started with a phone call on the holiday weekend to Donald and Rob Sobey, owners of the second-largest food retailer in Canada. Except this call wasn’t about food, or even particle astrophysics. It was about how philanthropists could help develop a new, low-cost ventilator to save lives amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The generosity of the individuals who helped us and their immediate response … I was flabbergasted,” said McDonald, who currently serves as professor emeritus at Queen’s University and won the Nobel Prize for his research into the mysteries of dark matter.

“I came away from those phone calls blessed by the response of those donors. It just made it possible for us to proceed. It was a race against time.”

This race began just a month earlier, in the very teeth of the pandemic.

Back in March, McDonald was contacted by Italian physicist and colleague Cristiano Galbiati, who was in lockdown in Milan – one of the virus’ epicenters at this time. He realized that elements of the technology they were developing in their particle experiments could potentially be applied to a new type of ventilator, one that can be produced quickly and at a relatively low cost.

Whereas a typical ventilator may include 1,500 parts, the proposed prototype would contain just 50 core components. Up to 1,000 units could be manufactured in a month.

With the virus spreading rapidly all around the world, experts soon realized there would be a shortage of PPE and ventilators to treat patients. While it may not have been McDonald’s usual area of expertise, here was a chance to make a contribution to the crisis, he thought.

Suddenly, some of the best minds in the world were rallied in the fight against COVID-19.

“All of them immediately said, ‘Whatever you need. We will be very willing to help out with this situation,’” he remembers.

“When we got into it, it was quite clear people with a wide variety of skills were pleased to apply them to do something positive to try and help.”

Financing needed

This international gathering of the minds, all volunteers, produced a functioning prototype at astonishing speed – 10 days.

Developing a full-scale, manufacturable, reliable and safe product, however, was another matter.

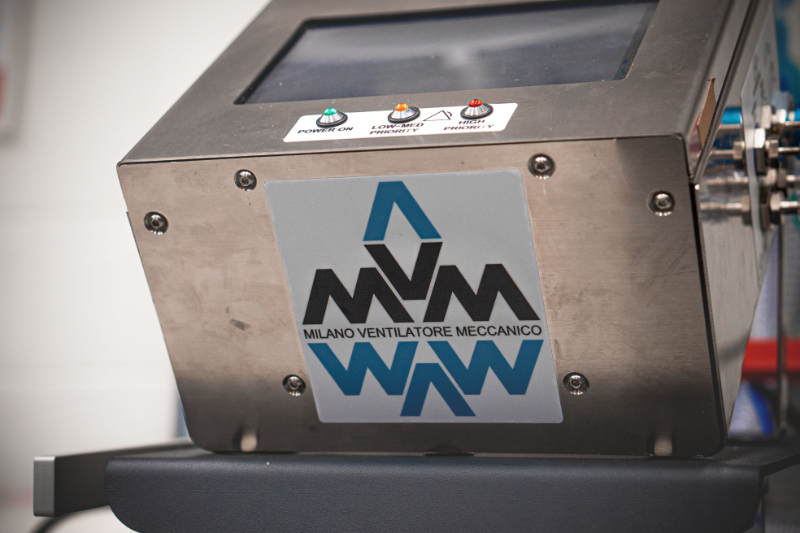

Dubbed the MVM Ventilator Project, McDonald and the international team set about finding companies that could actually manufacture the product. They decided on Vexos, based in Markham, JMP Solutions in London, Ont. and Elemaster in Italy.

In a true act of philanthropy, McDonald and his colleagues didn’t seek personal gain from the project. All of the research was deemed “open source,” which effectively allows any company in the world to use the design for the benefit of their communities.

Certainly, Canada was paying attention.

In early April, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that McDonald and his team would be one of four suppliers that the government could engage for ventilators, with the goal of boosting the country’s stockpile by more than 30,000 units.

So with a working prototype in hand, and a possible order from the Canadian government, the MVM Ventilator Project was off and running. It became a waiting game for the ventilators to receive full approval from Health Canada.

There was just one problem.

“With the demand for ventilators everywhere in the world, many critical components were in short supply,” McDonald explained.

“The companies supplying them were saying, ‘Fine, you can purchase them, but we want a full financial commitment.’ The government contract was 10,000 devices, but in April we needed to come up with the money to secure these components.”

So on that Sunday morning on Easter weekend, Donald and Rob Sobey gladly accepted the Nobel Laureate’s call. While both from the Maritimes, Donald and Rob were also Queen’s University graduates, where McDonald has been a professor since 1989.

By the end of the conversation, the Donald R. Sobey Foundation had made a substantial donation to secure the critical parts, paving the way for one of the most unique and timely partnerships in recent memory.

“I think the world is upside down,” Rob Sobey, a trustee of the Donald R. Sobey Foundation, told CTV News in April.

“Everything is back to front. And here is a really great example of science working with business to come up with new collaborations to get things done. To save lives. This is nothing more than saving lives. I think everyone hopes these ventilators won’t be needed. But it is certainly better to have them and not need them, than the other way around.”

Boosting donations

McDonald’s next call was to Peter Nicholson Sr., the chairman of The Foundation WCPD.

Nicholson immediately referred him to his son, Peter Nicholson Jr., the president and founder of The Foundation WCPD. As someone who lives and breathes philanthropy, here was someone who could reach more donors.

Since 2006, The Foundation WCPD – a boutique financial services firm – has worked with Canada’s largest philanthropists by using flow-through shares to help them give up to three times more than a standard donation at no additional cost. The firm combines two long-established tax policies: One to assist Canada’s resource sector to create jobs and produce raw materials, and another to give Canadians a tax break for donations to charity, or your standard tax receipt.

What it adds up to is more than $150 million in charitable donations by its clients to charities all across Canada.

“I immediately wanted to help,” said Nicholson Jr., whose company is headquartered in Ottawa. “I have been working with philanthropists for a long time, but this call was special. It was truly humbling to be asked and have the ability to help.”

In addition to making a personal donation, Nicholson quickly set up meetings with other philanthropists over Easter weekend. The Garrett Family Foundation, Josh Felker, Dan Robichaud, Patricia Saputo, Salvatore Guerrera, Nicola Tedeschi and four anonymous donors all contributed to the effort, as did the Lazaridis Family Foundation in answer to a personal contact from McDonald.

The Foundation WCPD’s tax structure helped boost the donations for some of these donors.

“Flow-through shares not only place a significant lever on your giving, but they also allow us clients to quickly laser those donations to a charity of their choice,” Nicholson explains.

Speed, as McDonald said, was indeed the name of the game. With hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations secured over a holiday weekend, his group could now guarantee the parts needed for the new, life-saving technology.

He also noted that some of the donations, held at Queen’s University in the Dr. Arthur McDonald Ventilator Research Fund, have been used to purchase a human lung simulator to help test the effectiveness of the new technology. Once COVID-19 passes, the equipment will be donated to the medical school, he said.

McDonald also wishes to use some of the donations to assist patients internationally, in places such as South America and Africa, where medical professionals are less-equipped to treat their patients.

Meanwhile, with Health Canada’s approval now secured, production has now begun on 10,000 low-cost, easy-to-manufacture ventilators – just in time.

As Canada settles in for a long winter and the second wave of COVID-19 sweeps across the country and the world, McDonald said he is both amazed and thankful to the donors for their rapid response. He adds that the ability to go from idea to final design to approval within regulatory agencies in just six months is “almost unheard of” and is a testament to society’s ability to pull together in times of crisis.

“I got the immediate impression of the big hearts who were making these quick decisions to support us,” McDonald said.

“I think it is quite unique in terms of the instant response on the part of the donors, at a very critical time for us. Their decisions were clearly made with a humanitarian objective, and I think we have been able to deliver on that vision.”

Read original article here